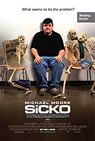

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Sicko (2007) Film Review

Passionate, partisan, polemical – Michael Moore is back with a new film almost certain to add to his status in some quarters as America’s Public Enemy Number One.

The mushrooming of anti-Moore sites and the recent documentary Manufacturing Dissent, which used his own methods to question his ‘selective editing’ approach, has obviously been water off the duck’s proverbial to him. Anyone expecting a more moderate, balanced tone to this examination of the American healthcare system will be sorely disappointed.

But anyone who likes a bracing blast of indignation against a target ripe for targeting will be reassured that Moore’s sense of outrage is as keen as ever, as is his showman’s instinct for what makes good documentary cinema.

One could argue that this time he has chosen an easier target than the ‘War on Terror’ (at times, Fahrenheit 9/11 did seem to simultaneously suggest that America should pull its troops out of Iraq and, er, send more in). Even its most vigorous supporters concede that a health system so geared towards private insurance can lead to anomalies and inequalities.

Wisely, Moore avoids focusing on those who remain outside the system. Instead his first case study is of a quintessentially decent, law-abiding American couple who diligently pay their healthcare premiums – but are hit by a massive increase when both become seriously ill at the same time, and end up living in their daughter’s spare room.

Yes, it’s manipulative to have the camera track them through all this, but seeing their suffering first-hand is a more telling indictment of the by-the-book bureaucracy of a vast, remote corporation than a thousand words of abstract argument.

He continues to provide examples of lives blighted by arbitrary decisions, or conscious policies of excluding ‘expensive cases’ to maximise profit. Some of the most telling testimony comes from whistleblowing former employees (often doctors or other medical professionals) who speak of a culture of exclusion where career advancement goes hand in hand with denying treatment to those greatly in need of it.

Of course, all this would be pretty dry if it weren’t for the constant stream of ironic archive footage and ‘hoist by their own petard’ quotes from the great and good. This aspect of the film does seem a little laboured now, probably because we’ve become so used to Moore’s particular style.

A more serious criticism comes when Moore takes off around the world to highlight how much better the ‘socialised medicine’ system is in countries like Britain, France and Canada. No doubt this plays very well among the right-on, right-thinking Americans who’ve still never been too far past their own borders. But a British audience, seeing his very selective and sanitised take on the NHS and remembering the latest wave of scandals and critical reports, may feel more like raising their hands and pointing out that our system isn’t perfect either.

But it is a salutary reminder that many of the things we take for granted are unavailable in America unless you pay through the nose. And, as Moore points out with some statistics to back him up, the system doesn’t even seem to be delivering, with the USA ranking very low in areas like infant mortality, longevity and incidence of the major killers like heat attacks and lung disease.

Of course statistics can be interpreted any way you like, and a universal healthcare system can create just as many anomalies and injustices. But the moment satire and polemic start saying: ‘on the other hand...’ they cease to be satire or polemic, and that’s as true for Moore’s detractors as the man himself.

In fact, for the climax of the film, Moore plays the patriotism card, contrasting the plight of the volunteer rescue workers at the World Trade Center (who, unlike the emergency services, were not covered for health problems sustained as a result of their heroic efforts) and the terror suspects held at Guantanamo Bay, who have access to state of the art healthcare free, gratis and for nothing.

Yes, putting the workers on a fleet of boats and heading for Cuba to ask for free treatment through a loudhailer is a ‘stunt’. And then taking advantage of the Castro regime’s healthcare system in another suspiciously spotless clinic does give a feeling of ‘who’s manipulating who?’ But none of that invalidates Moore’s central point; that these people, and all the other ‘excluded’, should not be in this position in the first place.

If this film encourages Americans to ask a few more questions as to why politicians, providers and drug companies seem so reluctant to countenance any change to the system, Moore would no doubt say the end has justified the means. And, love him or hate him, a world in which these questions couldn’t be freely asked would be an unhealthy one indeed.

Reviewed on: 23 Oct 2007If you like this, try:

Bowling For ColumbineFahrenheit 9/11

Manufacturing Dissent: Uncovering Michael Moore